Hardhat Tells the Story of Medical Professionals at Ground Zero

Hardhat Tells the Story of Medical Professionals at Ground Zero

“Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.” – Mister Rogers

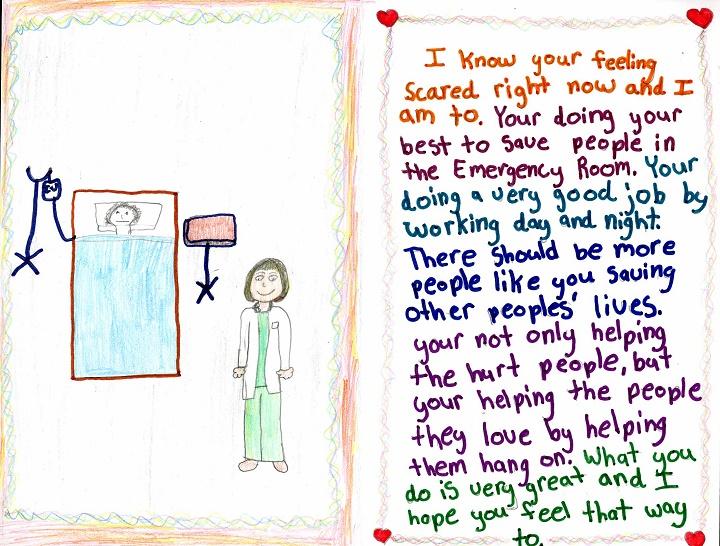

One of the first donations to the nascent 9/11 Memorial Museum in 2006 was a collection acquired from the American Red Cross September 11 Recovery Program, which consisted of hundreds of drawings and cards made by children. Many suggest the guidance of Mister Rogers (Fred Rogers; 1928–2003), the beloved television personality who advised young people to always “look for the helpers,” in times of trouble. Accordingly, these artworks saluting the helpers of 9/11—often addressed to “Dear Heroes”—are populated with a familiar cast of firefighters, police officers, and construction workers, as well as doctors, nurses, and Red Cross volunteers.

But what if the helper isn’t identifiable through a uniform or another visible cue identifying him or her as a responder? This was the problem Dr. Todd Wider confronted as he neared Ground Zero on the afternoon of September 11.

A specialist in complicated reconstructive surgery, Dr. Wider divided his time between a busy practice in plastic surgery on Fifth Avenue and Roosevelt Hospital (now Mt. Sinai West) on the Upper West Side, where he was an attending physician.

Still at home when he overheard a CNN report about a plane crashing into one of the Twin Towers, Wilder initially assumed that “some jackass flew his Cessna into the building,” according to an account he wrote about his fateful day, contributed to the Museum. Continuing to glance at the live news coverage from the World Trade Center, he was shocked, minutes later, to witness a second aircraft torpedoing through the South Tower. A message began scrolling across the bottom of his television screen declaring a state of emergency in New York City and requesting all medical personnel to report to their respective hospitals.

Slipping on hospital scrubs, a sweatshirt, and a lab coat, Dr. Wider raced across town to Roosevelt Hospital. Along with 50 to 60 other doctors, nurses, and medical technicians converging at the emergency entrance on 10th Avenue and 58th Street, he stood vigil outside, preparing to assess and treat injured survivors arriving by ambulance. Gurneys stood ready. The hospital’s operating rooms were prepped. Intense triage activity would soon be underway.

As the morning wore on, however, the caseload of patients failed to appear. Rumors began to circulate about various biohazardous threats, suspected truck bombs, and hospitals as the next terrorist targets. As dust-covered evacuees appeared from downtown, seeking rest on the benches and grass outside the hospital, Dr. Wider found a bullhorn and instructed them to head toward the river or into the city parks, away from any conspicuous landmarks.

By the early afternoon, only a few survivors with minor burns had cycled through Roosevelt’s emergency room. In a doctors’ lounge, Dr. Wider caught up with the day’s continuing televised coverage, which is how he learned about the third and fourth hijacked aircraft and their deadly crashes into the Pentagon and a remote field in western Pennsylvania. “We were in a new kind of war,” he thought.

Having previously performed surgery under challenging conditions in Nepal and Guatemala—at times, operating by flashlight—and with a decade’s experience treating gunshot and drug violence victims at the triage center of another large Manhattan-based hospital complex, Dr. Wider felt primed to respond to the casualties of the terror attack in lower Manhattan.

But staying uptown held decreasing promise for putting his skills into action. He made an independent decision to redeploy downtown and retrieved his car from the hospital’s parking lot, hoping that his MD license plates would expedite his ride south down the West Side Highway. After clearing several checkpoints, he briefly stopped at Chelsea Piers, designated as a treatment hub for volunteers with medical skills. Encountering more doctors and nurses awaiting instructions rather than injured arrivals, he left the Piers determined to maneuver his way closer to the disaster scene.

Abandoning his car a few blocks north of the Trade Center, Dr. Wider emerged from the vehicle into a landscape of gray ash, smoke, and debris—a startling shift from the sun-soaked locale uptown he had exited earlier. He made his way to a newly established triage center at Stuyvesant High School where he encountered several other medical professionals, included a surgeon who had been a former junior resident under his tutelage. There was little traffic through the school, however, fueling Dr. Wider’s restlessness. Assuming that anyone pulled from the rubble alive would need first aid, he headed outside toward the 16-acre war zone. Later, he would compare what he encountered to “a surreal science fiction movie… as if some giant, fire-breathing monster had march through downtown, laying waste to everything in sight.”

Plastic hard hat with cap-style brim and interior suspension. The hard hat is yellow with a red cross on the front created with duct tape. The hard hat is slightly dusty.

He saw few masks in use, and no goggles. But someone handed him a plastic yellow hard hat—the sole piece of protective equipment he was fortunate enough to acquire. With skills to offer other than cutting steel or dousing fires, and with poor visibility and acoustics to contend with, Dr. Wider grasped the imperative to announce himself as a qualified physician. Necessity required inventiveness. Remarkably, a roll of red duct tape materialized. With two quick tears, he improvised the universal “red cross” symbol above the hat’s brim.

Dr. Wider remained at the edge of the collapse pile all night and through mid-morning Wednesday, flushing out eyes, dressing cuts, administering IVs, and distributing water to the exhausted rescue personnel. As he backtracked out of the Frozen Zone, reporters flocked to him, asking about the conditions he had experienced. Wearing his improvised medical helmet, he stated emphatically that rescuers on frontlines required better masks, respirators, goggles—and more ophthalmologists.

Todd Wider’s brief but intense experience at Ground Zero humbled him. Newly appreciating fate’s unpredictable workings, he became inspired to explore personal interests other than medicine, including producing documentary films probing humanitarian issues. In 2016, he decided to donate his providential helmet to the 9/11 Memorial Museum. By doing so, he wished to acknowledge all the resourceful volunteers—including trained medical personnel—who had answered the call at the World Trade Center site in the awful aftermath of 9/11 and to commemorate the influence of this pivotal interaction on his own journey forward, seeking purpose by helping others.

By Jan Seidler Ramirez, Executive Vice President of Collections & Chief Curator, 9/11 Memorial & Museum

Previous Post

“The Stories They Tell” Video Series Lends History and Humanity to Museum Artifacts

The Museum’s “The Stories They Tell” video series provides a way to learn more about the Museum’s artifacts by hearing directly from the family members, survivors, first responders, and recovery workers connected to those objects.

Next Post

Mission To Remember Video Series Takes You Behind the Scenes of the 9/11 Memorial & Museum

The 9/11 Memorial & Museum Mission to Remember video series offers a behind-the-scenes look into one of the most sacred sites in the world.