Remembering March 2, 2001: The Destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas

Remembering March 2, 2001: The Destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas

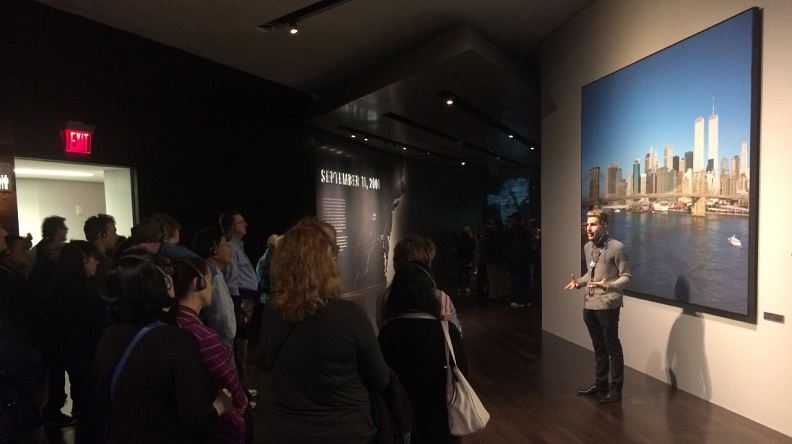

On a state visit to the United States in January 2002, Hamid Karzai—chairman of the interim administration of Afghanistan and future president of Afghanistan—laid a wreath at Ground Zero and presented U.S. President George W. Bush with a plaque from the people of Afghanistan. Engraved with the words “Terrorists Are Destroying World Civilization,” the plaque depicts a Buddha statue, wreathed in smoke, in front of the burning Twin Towers. The imagery alludes to an event that occurred six months before members of al-Qaeda hijacked four planes and flew them into symbols of American culture and power. In March 2001, the Taliban, an Islamist fundamentalist group that ran Afghanistan, began a weeks-long assault on two treasured symbols of the country’s pre-Islamic heritage: the Bamiyan Buddhas.

Plaque presented to the people of the United States from the people of Afghanistan, January 28, 2002. Courtesy of the George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum.

More than 1,500 years ago, the Bamiyan Valley of Afghanistan’s central highlands was a vibrant Buddhist monastic center—a destination for pilgrims and stopping point on the ancient Silk Road, where traders and travelers exchanged goods and ideas from both East and West. People came to Bamiyan to worship, to learn, and to see the two colossal Buddhas carved into the valley’s sandstone cliffs. Standing about 175 feet high, the Buddha on the western end of the cliffside was taller than the Statue of Liberty from base to torch, and the eastern Buddha measured about 120 feet tall. Dating to around the fifth century CE, the Buddhas reflected Indian, Central Asian, and Greek and Roman influences. The statues were covered in stucco and painted dazzling colors, leading one seventh-century monk to report that they were made of gold and copper and adorned with precious gems. In the cliffsides surrounding the massive Buddhas, hundreds of caves served as chapels and places of contemplation for monks and pilgrims, with colorful murals covering the walls and ceilings.

The Bamiyan Buddhas stood for more than a millennium, surviving Mongol ruler Genghis Khan’s destruction of the city in 1221 CE and later defacement in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. In 2001, however, they fell. In late February of that year, Taliban leader Mullah Mohammad Omar—possibly encouraged by al-Qaeda—ordered the destruction of Afghanistan’s famous Buddha statues, declaring them “insulting to Islam.” Heads of state, religious leaders, and cultural heritage advocates around the world pleaded with the Taliban to save the Buddhas; New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art even offered to buy the statues if that would ensure their preservation.

Taliban leaders refused.

Beginning on March 2 and continuing for weeks, Taliban troops launched an all-out assault on the Buddhas, firing at them with guns, tank shells, rocket launchers, and anti-aircraft weapons. When this only succeeded in damaging the statues, they ordered men to drill holes into the Buddhas and plant explosives that would destroy the ancient figures once and for all. By the end of March 2001, the Bamiyan Buddhas had been reduced to piles of rubble, the only sign of them the empty niches in the cliffsides where they had stood for 1,500 years.

“The Afghans understand America’s pain,” Hamid Karzai said when he visited Ground Zero in January 2002. Within six months of each other, both countries had seen iconic cultural centers demolished in the name of Islamist extremism. The Taliban’s actions in 2001 also provided a model for more recent acts of cultural destruction. In the last decade, the Islamic State (also known as ISIS or ISIL) has looted and destroyed churches, mosques, museums, and historic sites across Iraq and Syria. Like the Taliban before them, their goal was to assert the dominance of their ideology by obliterating the history and culture that came before their regime.

This March, the 20th anniversary of the Bamiyan Buddhas’ destruction, provides a sobering reminder that violence and terrorism continue to threaten humanity’s shared cultural heritage. Yet it also presents an opportunity to reflect on the beauty that can come out of peaceful cultural exchange—like the meeting of people and ideas that created the Bamiyan Buddhas so many centuries ago.

By R. Isabela Morales, Manager of Exhibition Development, 9/11 Memorial & Museum

Previous Post

Learn from the Experts in New “Ask an Educator” Program

The 9/11 Memorial & Museum has launched “Ask an Educator,” a brand-new virtual school program for students in grades 3–12.

Next Post

Stories of Hope: The Good That Connects Us

Some thought New York City would never recover from 9/11, but it did, and it came back stronger than before. We will come through the challenges we face today, we’ll bear the scars, we’ll remember the ones we lost, but we will come through it.