Rescue & Recovery: In Their Own Voices With Elizabeth Cascio

Rescue & Recovery: In Their Own Voices With Elizabeth Cascio

- March 30, 2023

In honor of Women’s History Month, Elizabeth Cascio, a trailblazer in her field, shares some stories from her 39-year career with the New York City Fire Department (FDNY). She was originally appointed as an EMT in 1984. For the next 30 years, she served as an EMT, EMS 9-1-1 Dispatcher, EMS academy instructor, and lieutenant. Cascio planned to retire in 2014 but was sought out by then-Commissioner Daniel Nigro to be his executive officer. In 2018, she was promoted to Chief of Staff, becoming the first female and EMS member to rise to each of those positions. Last month, Cascio retired after nearly four decades of service. In that time, she responded to both the bombing of the World Trade Center in 1993 and the attack on September 11th. As part of our "In Their Own Voices" series, Cascio talks about the EMS academy mobilization in response to the attacks, and her experience as a 9/11 cancer survivor.

Cascio (center) with her partner, then-EMT Jimmy Mondello (right), and members of the FDNY.

Where were you on 9/11?

The morning started just like you will hear everybody else who is a survivor or responder say, as a beautiful late summer day. It was a strikingly beautiful day: blue, blue skies without a cloud in sight and the perfect temperature. It was so beautiful. I remember grabbing my morning coffee to sit outside for a few minutes just to take it all in.

I was back in my office for 20 or 30 minutes before an officer who worked with us at the academy ran in and asked, “What’s going on at the World Trade Center? Someone called for every available ambulance to respond.” We started making some phone calls, but nobody picked up. We turned on the TV and see the smoke billowing out of the building. The newscaster said a plane accidentally flew into the tower. This was confusing, because it was such a clear day and it seemed impossible to not see these huge buildings.

As we continued to watch, we saw the second plane hit the other tower. We knew in that moment we would mobilize the academy to respond, just like we did in 1993, but on a larger scale. When we mobilized the academy, we got every vehicle we had, including all ambulances. We also commandeered two MTA buses. All of us — every staff member and student — got on those vehicles. The first tower collapsed while we were en route to Manhattan.

While on the buses, we were monitoring the radios from the scene. We were listening to responders who were trapped. We also heard the dispatcher do a roll call to get anyone with a radio at the scene to answer. Nobody answered. Eventually, it was a chief who was making his way to the World Trade Center on foot from Brooklyn who responded on the radio. It was a sobering moment. We believed everyone was dead.

We finally got into lower Manhattan, and as we were turning onto West Street by Stuyvesant High School, the second tower came crashing down and engulfed us. At the time, we thought there would be hundreds, if not thousands, of patients. We started to set up a war triage center. Within an hour or two, you could tell there weren’t many people to transport to hospitals. Those who were able to self-evacuate did so. We spent the rest of the day and night at the site. There were times we got so tired, we were just sitting in the ash, which was at least a foot deep. At the time, we knew it wasn’t safe. We knew it was a hazardous materials scene, but there wasn’t much you could do about it.

What role did you play in the rescue and recovery efforts?

We decided right away that the EMS academy was going to assist the effort. We mobilized a group of different instructors who were each assigned a partner and a different area of the pile. Using gators, we would drive them as far into the pile as we could get. We would remove any remains found and bring them to the on-site temporary morgue. We did that every day in September. I spent the month by Engine 10, Ladder 10, with my partner.

For the first couple of days, we really thought we were going to find people. We thought as debris was being moved, we would find people in these pockets. It was a short-lived belief. First, we realized there was nothing recognizable in this pile of debris. These were two huge buildings of office space and there were no desks, chairs, file cabinets, or phones. There was nothing that would make you think this was once all office space. The other thing we realized was that as debris was moved, and as the area was exposed to oxygen, fires would ignite. With all that burning underneath, there couldn’t possibly be people who survived.

Do you have any health issues related to your time at Ground Zero?

In October 2001, I start to have this chronic cough, which I referred to as my "Ground Zero cough." Many people would say, “Don’t say that.” Then other people started coughing, too. That was the first indication that we had had some significant exposures and connected health issues.

In January of 2002, I reported to FDNY headquarters for my annual medical. This time, it was different. Dr. Kelly, who was the Chief Medical Officer for the FDNY, made sure everyone signed up for a World Trade Center health monitoring program. We signed a lot of consent forms so they could do research and studies, and they did baseline exams that could be used to compare as the years went by.

There are many people who have gotten sick for their time at Ground Zero, I am one of them. I am a 9/11 cancer survivor. In 2019, I was diagnosed with invasive cervical cancer. It is one of the reproductive system cancers classified by the WTC Health Program as a 9/11 cancer. However, it wasn’t classified until late 2013. Since there was less representation of women in the roles of first responders, it took a longer amount of time to study the group to see if they were having a higher incidence of illness than the general population.

Why is it so important that future generations learn the story of 9/11?

When I was on the pile, I was walking with my partner, Jimmy, and we were waiting for someone to be found. We were taking in the entire scene, and I turned to Jimmy and said, "I get what it means to say 'Never Forget'. This is what they mean. I get what it means when the WWII vets say 'Never Forget'."

When I think about it, the idea of talking about this is difficult for me, however, I feel a sense of duty and a sense of responsibility. That’s what "Never Forget" means to me. Making sure the story doesn’t die with the people.

Is there anything else you'd like to add?

My whole world is defined by pre-9/11 and post 9/11. My new world is defined by COVID. No one could have told me early on that my career would include pandemics and terrorist attacks, plus the everyday responsibilities of helping in weather related emergencies, people in cardiac arrest, victims of crime, and so on.

Also, if there is nothing else that I’ve learned from this experience, I’ve learned about the emotional toll of being a first responder and prioritizing mental health. I learned the key to success, particularly for a long-term career as an EMT, is resilience. That’s not a skill that can be taught. Instructors can tell you why it’s important, but we can’t teach you how to develop that. Resiliency is being able to take in these experiences and still be able to function, whole, healthy, and useful.

My advice is to always be a student. I’m still learning. As long as you’re still learning, you’re still growing.

Compiled by Caitlyn Best, Government and Community Affairs Coordinator

Previous Post

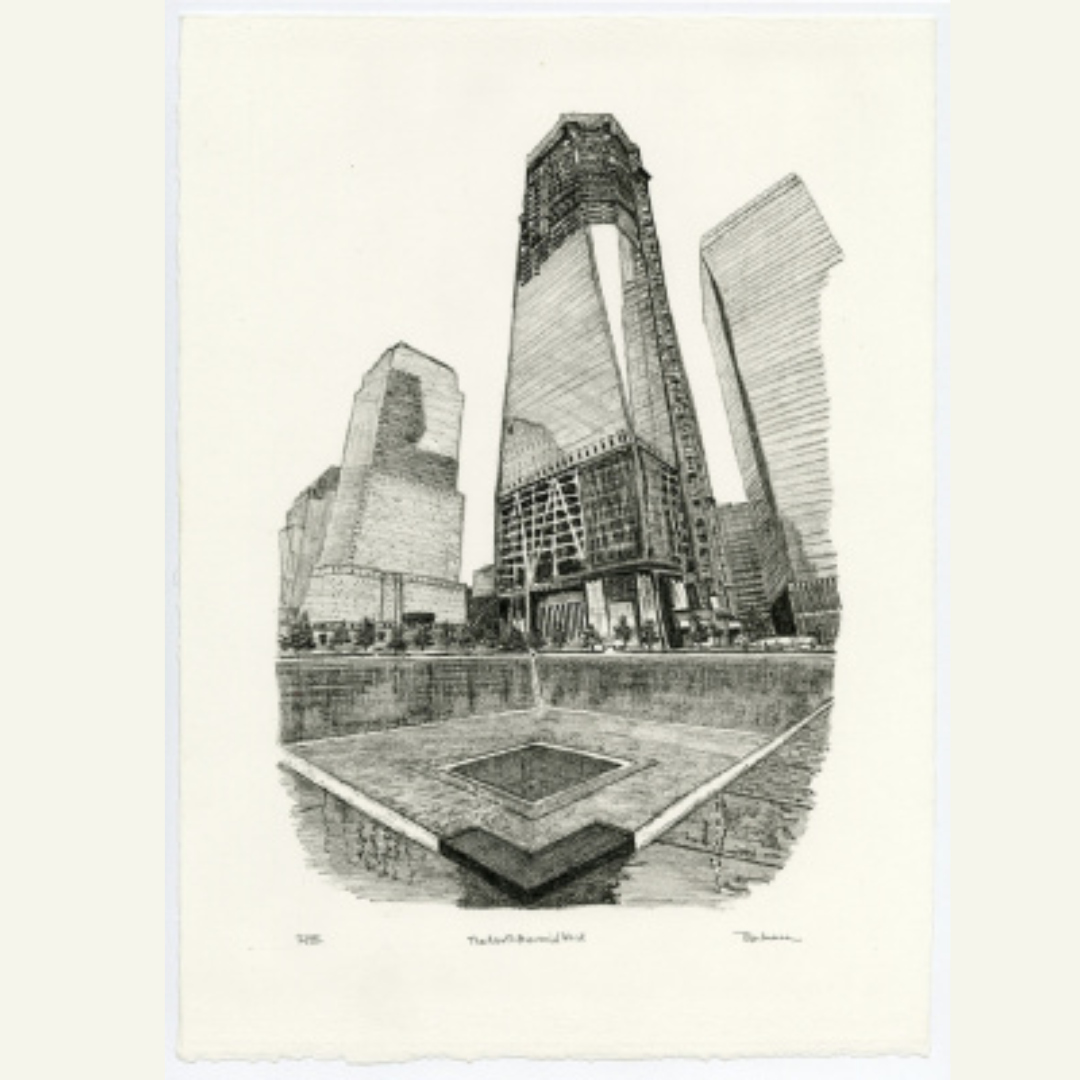

Towers Rising, Through the Eyes of First Responder Turned Artist

First Responder Brenda Berkman, an FDNY Lieutenant, channels the personal trauma of 9/11 into art that reflects the changing skyline — and resilience — of New York City since the attacks.

Next Post

Rescue & Recovery: In Their Own Voices With Bram Gunther

With Earth Day front of mind, we're highlighting Bram Gunther, Deputy Director of Forestry and Horticulture for the New York City Parks Department on 9/11, in the April installment of our "In Their Own Voices" series. Gunther talks about his role in saving the Callery Pear that became the Survivor Tree and what trees and nature in general can do for those grieving in a time of crisis.