Slurry Wall: Behind the Engineering Feat That Made the WTC Possible

Slurry Wall: Behind the Engineering Feat That Made the WTC Possible

In 1614 early Dutch settlers of Manhattan landed on the shoreline of the Hudson River near what is today Greenwich Street, just east of the 9/11 Memorial & Museum. Over the past 400 years, Manhattan’s footprint has expanded outward, having been filled during various periods of development with demolition debris, marine construction, abandoned ships, and city waste.

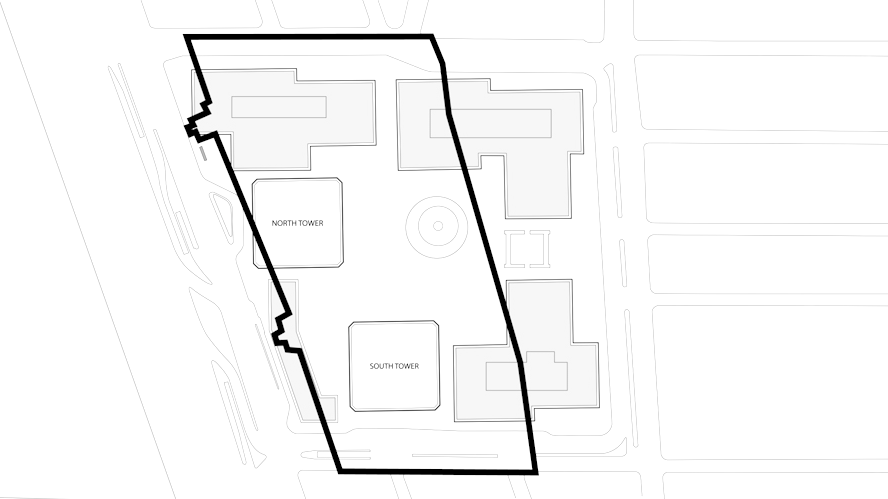

As construction of the World Trade Center was commencing in the 1960s at a 16-acre area of landfill known as Radio Row, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey had to determine a way to build the two largest skyscrapers in the world on a site that was once submerged within the Hudson River. The solution to this challenge was to employ an innovative Italian construction technique—never before used at this scale in the United States—known as the slurry wall method. This involved building an underground perimeter wall that would stop the entry of river water into the site and permit excavation down to bedrock, where the Twin Towers’ foundations would be built.

The slurry wall method was patented in Italy in the late 1940s by the ICOS Company. It was then introduced during construction of Milan’s subway system in the 1950s. The technique was brought to the United States in the 1960s and used on small projects before being employed at a larger scale for the construction of the World Trade Center in 1967.

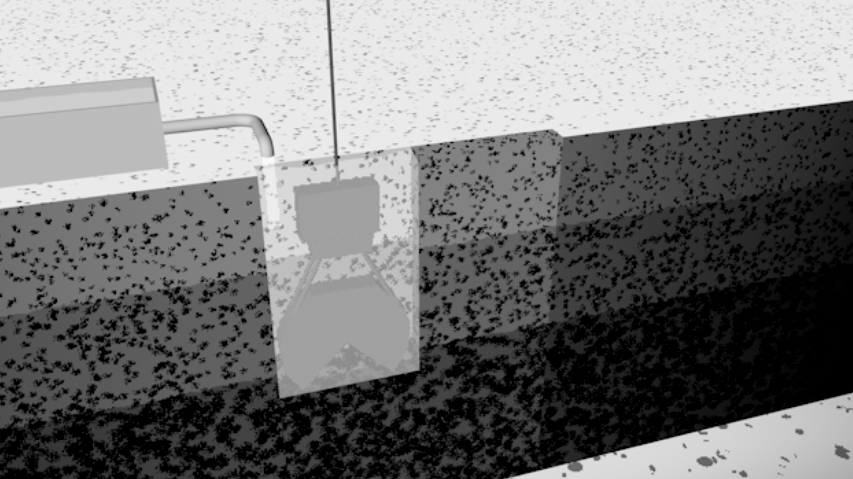

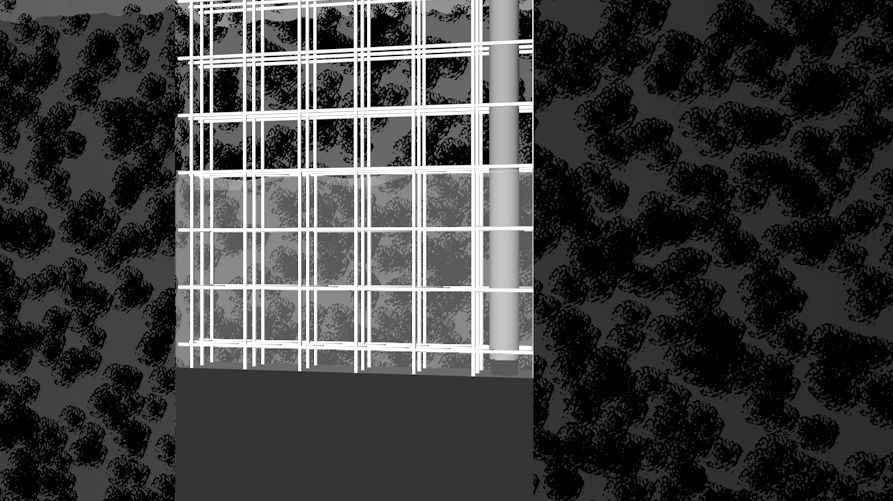

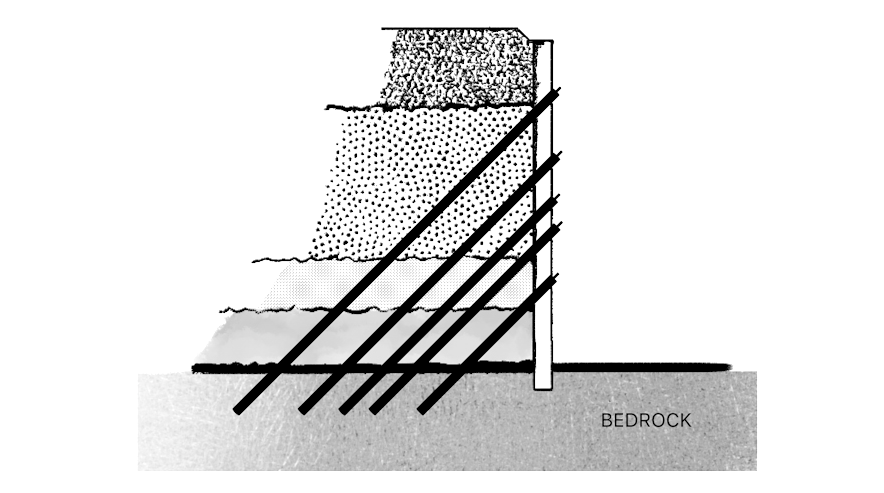

Though a state-of-the-art engineering technique, slurry wall construction is surprisingly simple. First a trench is dug using a mechanical clamshell excavator. As digging progresses, bentonite slurry—a liquid clay dense enough to keep out groundwater and hold the walls of the excavation from collapsing—is injected into the trench. At the World Trade Center site, construction crews dug 70 feet below the surface to reach bedrock, at which point a rock chisel was used to cut a keyway into the rock. The digging is done in panel-length sections, each measuring 3 feet wide, 22 feet long, and 70 feet deep. Once the excavation is complete, a steel cage is lowered into the slurry-filled slot in the ground and concrete is pumped through a pipe to the bottom of the trench. The concrete fills the trench and displaces the slurry, which is recycled for use on the next panel. Construction is done panel by panel until an enclosed perimeter wall is cast into the earth. Approximately 158 panels enclosed 11 of the 16 acres of the World Trade Center site.

Once the concrete cures, excavation can begin in the area within the slurry wall. As soil is removed, the lateral support for the wall is also removed. When the site is excavated 10 to 15 feet below the surface, tie-back anchors are installed to keep the wall from collapsing inward. To install the tie-backs, six-inch-diameter casings are drilled diagonally through openings cast in the wall, and then through the earth and into bedrock on the outside of the wall. Steel tendons are inserted into the casings and then socketed and grouted into the bedrock. The tie-backs are then tensioned, tested for strength, and locked into place to hold the wall. At the World Trade Center, this process was repeated level by level until the interior of this perimeter wall was cleared down to bedrock and the spoils trucked across West Street to form part of what is now Battery Park City. The completion of this process revealed what came to be known as the “bathtub,” a deep basement bounded by a water-tight perimeter wall measuring 3,500 feet in length.

The scale of the World Trade Center slurry wall was unprecedented and remains one of the most challenging foundation construction projects in New York to this day. Its success however helped prove a concept and the slurry wall method is still used on foundation projects throughout the world.

By 9/11 Memorial Staff

Previous Post

Former CIA Targeter to Discuss Tracking Down Terrorists in Public Program

On Monday, November 25, the 9/11 Memorial & Museum will host Nada Bakos, author of The Targeter: My Life in the CIA, Hunting Terrorists and Challenging the White House, in a public program in the Museum Auditorium.

Next Post

Thanksgiving Traditions, Memories Have the Power to Heal

Thanksgiving can be bittersweet for 9/11 family members, as they remember time spent with those they’ve lost. These three accounts show how our Thanksgiving traditions are both unique and universal in their power to comfort and heal.